News

02 March 2022

New research, led by ICTS scientists, use observations of gravitational waves to probe the nature of the enigmatic ‘dark matter.’

One of the biggest puzzles in modern cosmology is the existence of dark matter, which constitutes most of the matter in the universe. Recent research by an international team of researchers, led by the ICTS group, has used gravitational waves to probe the nature of dark matter. This work was published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Dark matter

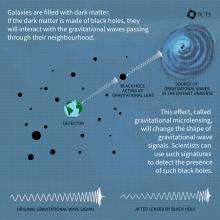

Several astronomical observations have established the existence of dark matter, which interacts with normal matter only through gravity. Dark matter does not emit any light and hence evades a direct astronomical observation. Galaxies, including our own Milky Way, are embedded in a halo of dark matter, whose size extends much further than the visible galaxy.

The Standard Model of Particle Physics describes all the elementary particles that constitute all the normal matter. Particles that are not described by the Standard Model could exist in the universe and could constitute dark matter. Several large experiments have been trying to detect such elusive particles over the past few decades, without success.

Another possibility is that dark matter comprises a large number of massive and compact objects, such as primordial black holes. Such black holes are different from the black holes that astronomers typically observe, which are produced by the death of massive stars. Primordial black holes are formed in the early universe and could exist in a variety of masses. They could be as light as asteroids or could weigh trillions of solar masses!

However, astronomers haven’t made a conclusive detection of primordial black holes. Also, various astronomical observations have constrained the abundance of primordial black holes. For example, such black holes could bend light from distant stars; a phenomenon called gravitational microlensing. Till now, scientists have been unsuccessful in observing microlensing produced by such black holes, despite searching extensively. This means that black holes that are much lighter than the Sun, which would have caused microlensing of starlight, are rare. Even if they exist, they would constitute only a very small fraction of the dark matter. Nevertheless, it is quite possible that black holes of some other masses could be contributing to dark matter.

Microlensing of gravitational waves as a new probe of dark matter

Recent observations of gravitational waves have provided astronomers with a new way of observing the universe. Gravitational waves are ripples in spacetime travelling with the speed of light. The observatories LIGO and Virgo, located in USA and Italy, have observed around hundred gravitational-wave signals over the past few years.

According to Einstein’s theory, gravitational waves are also bent by massive objects in between the source and observer. If a significant fraction of dark matter is in the form of black holes, they should cause microlensing effects in the observed signals. Microlensing will distort the gravitational waves in a manner scientists can calculate exactly. However, the international team could not observe any such distortion in the signals observed by LIGO and Virgo.

The present work uses the non-observation of such lensing effects in the gravitational-wave signals to assess what fraction of the dark matter could be in the form of black holes. The black holes that cause microlensing of gravitational waves are much more massive than those that cause microlensing of light. The scientists conclude that only less than half of the dark matter could be in the form of black holes within the mass range of 100 to 100,000 solar masses. This is an upper limit; the actual fraction can be much smaller.

Future observations

The current constraints from gravitational-wave lensing observations are not as tight as compared to those obtained from other astronomical measurements. Other observations, such as the cosmic microwave background, tell us that such massive primordial black holes could contribute only a much smaller fraction of the dark matter. However, there are two reasons for scientists to get excited about this method. First, each observation comes with its own errors; it is important for scientists to arrive at the same conclusions using different observations and experiments. Second, gravitational-wave observations will be able to provide much better constraints in the near future.

In the next few years, LIGO and Virgo, along with upcoming detectors such as KAGRA and LIGO-India, will observe thousands of gravitational-wave signals. If scientists do not observe any signatures of microlensing in these gravitational wave signals, they will be able to conclude that only a very small fraction of the dark matter could be in the form of such heavy black holes. On the other hand, if a good fraction of the gravitational-wave signals contains signatures of lensing, this would be a smoking gun evidence of the much sought after primordial black holes. Either way, microlensing of gravitational waves offers a unique way of probing the nature of dark matter.

This research was supported by the Department of Atomic Energy, Government of India, under Project No. RTI4001 to the International Centre for Theoretical Sciences (ICTS) of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, by the Simons Foundation through a Targeted Grant to ICTS, by the Max Planck Society through a Max Planck Partner Group at ICTS and by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research through the CIFAR Azrieli Global Scholars program. The numerical calculations reported in the paper were performed on the Alice computing cluster at ICTS and the Sarathi cluster at IUCAA.

Contact:

- Parameswaran Ajith <ajith@icts.res.in> (Principal Investigator)

- Soummyadip Basak <soummyadip.basak@icts.res.in>

- Apratim Ganguly <apratim@iucaa.in>

- Shasvath Kapadia <shasvath.kapadia@icts.res.in>

- K. Haris <haris.k@ligo.org>

- Ajit Mehta <ajit.mehta@aei.mpg.de>

Infographic credit: Roshni Samuel / Parameswaran Ajith / ICTS